The most authentic portrayal of both the paisa dialect and the cultural atmosphere of Medellín is illustrated through Luis Miguel Rivas’ novel, “era más grande el muerto.” The story follows the daily lives of ordinary characters, like two young men who buy and resell luxury clothing from the morgue, a mob boss who falls in love with an average woman, and a hitman who’s searching for his already deceased target. These characters and their relationships, rather than an out-of-the ordinary occurrence, drive the plot of the story, demonstrating how paisa culture is dependent on interactions and social ties, rather than individualistic value and extraordinary personal attributes.

Rivas uses accurate phonetic and semantic features throughout the novel to create an authentic representation of the lives led by the people in this region. The novel itself is a conversation between the author and the reader; the tone is relaxed and the personality of the characters are on display with every sentence the reader absorbs. The author doesn’t attempt to glamorize or hide any aspect of Colombian reality through inaccurate speech samples or larger-than-life characters. Instead, the book serves as a genuine and authentic celebration of the paisa dialect and culture. It carries the spirit of Medellín.

Let’s take a look at a few of the unique speech characteristics throughout the novel:

The diminutive (“diminutivo”):

In Spanish, the diminutive is a suffix that modifies a noun to serve a purpose, like making something seem smaller and cuter.

Using the diminutive in the story:

In paisa gang culture, emotions are rarely expressed directly through words, so the use of the diminutive adds an element of trust, security, and solidarity (“confianza”) between male characters, while maintaining their personal appearance of strength and machismo. For example:

- “dame un guarito sencillo…”

- “mamacitas” who have “la piel suavecita” and “la hojita del talonario”

- “musiquita americana movidita”

Female characters in this novel rarely use the diminutive, making it a more masculine attribute. Instead, men commonly use it to describe women, which highlights the inequality between the two genders, where men are expected to adhere to “machismo”, avoiding emotions, whereas women are portrayed as tiny, delicate, and therefore, less powerful.

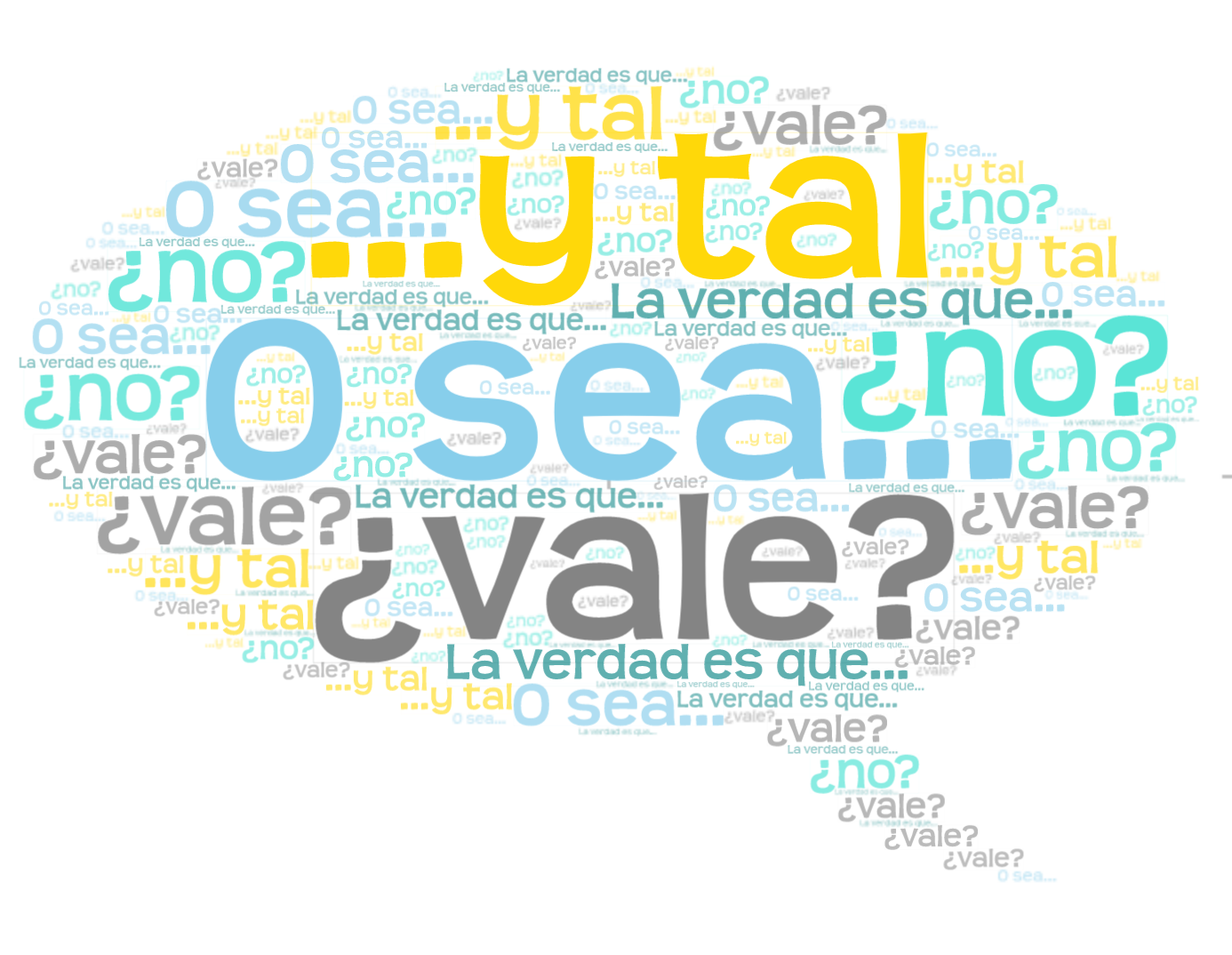

“Filler” words (“Muletillas de conversación”):

Throughout the novel, paisas incorporate “filler” words throughout the sentences they speak. For example:

- “no, pues tan picada esta pelitenida”

- “vamos pues que se nos va”

- “¿vos crees que yo soy guevón o qué?”

- “Es que lo que pasa es que…”

- “vea, yo le presto de esta plata que tengo”

All of the above phrases immerse the reader directly into the culture, making him/her feel as if they are engaging in a conversation between friends, rather than simply reading a novel as a third-party spectator. In this way, the reader is involved in the action and the lives of the characters. This illustrates the collectivist nature of Medellín, where everyone (including the reader) is socially connected; one cannot exist in this society without social ties.

Elision (“Elisión”):

Another linguistic characteristic that immerses the reader directly into the novel is elision, which occurs when a sound or syllable is omitted from a word or phrase.

/blackboard_syncope-lg-58b9a34d5f9b58af5c801a53.jpg)

One of the most common syllable omissions throughout the novel occurs with the word “para.” Phrases like “pa’qué tanto,” “cuando uno se tira en la manga a mirar pa’rriba,” and “antes de irse pa’la casa” allow the reader to “hear” the spirit of Medellín and gain an authentic understanding of the culture.

Rivas also implements the omission of the /d/ in the word “pelado,” which transforms it into “pelao.” Notably, this omission never occurs with the feminine version of this word, “pelada.” The word itself literally translates to “hairless,” and is used to refer to adolescent boys and girls, who have yet to go through puberty and grow hair, which would mark them as adults. Until they grow this hair, they are inferior to their elders, who have more experience, money, and power than them. For this reason, older characters often use “pelao” in commands to reinforce the existing power imbalance and social hierarchy:

- “pelao, tráigame un trago”

- “pelao, préndame este cigarrillo”

- “pelao, amárreme los zapatos”

- “pelao, bésame los pies”

Nicknames (“Apodos”):

As illustrated through the film “la vendedora de rosas,” nicknames are crucial to paisa culture, providing a sense of interconnectedness and camaraderie. Medellín exists as a collectivist system depending on social ties and relationships, rather than individual success; for this reason, relationships are on display for all to see in this region and everyone exists as a connection to someone else. Rivas illustrates this concept throughout the novel. Let’s quickly examine some of the most common nicknames used:

- “hijueputa” – occuring in various contexts, this nickname serves both as an insult and as a respectful term throughout the novel. Notably, it’s the mantra of the working class, as most of the interactions between ordinary men include “hijueputa.” Everyone seems to be a “hijueputa:” friends, enemies, business partners, family members. Although it can be used as an insult, it still shows group affiliation, instead of isolating individuals.

- “malparido” – similar to “hijueputa,” this nickname can be an insult or a term of camaraderie. Characters strive to be “malparidos” in camaraderie, rather than “malparidos” in bad blood.

- Words for women: “mamacita” and “mona” – these nicknames are used to refer to women throughout the novel. In particular, male characters utilize these names in tandem with physical descriptions, which reinforces the sexism at play in paisa culture. Women seem to be most valued for their bodies and physical appearance.

- Words for men: “man,” “orangutanes,” “chichipato,” “home,” “hombre,” and “maricón” (among others…) – the number of nicknames for men far surpasses that of the women, indicating the prevalence of machismo and gang culture in this region. Men refer to each other with various nicknames, indicating camaraderie, friendship, and relational ties.

- “parce”/”parcero” – these two nicknames are used among friends and acquaintances, demonstrating camaraderie and collectivism. Everyone exists as a “parcero” to someone else. Nobody exists solely as an individual, without a “parcero.”

Address Forms (“formas de dirección):

Paisas use various forms of addressing each other, depending on the context of the conversation and the relationship between the two speakers. Let’s take a peek at typical pronouns used throughout the novel.

The pronoun “vos” is usually implemented between paisas and acquaintances, for example:

- “Es que vos sos demasiado chichipato para estos lugares”

- “¿Y si vos sos tan tantán qué hacés andando con chichipatos?”

Here, “vos” serves to indicate mutual respect, creating an immediate relationship between two characters, simply by means of speaking like a paisa. “Vos” creates social ties, which contribute to the collectivist nature of Colombia.

Throughout the novel, the pronoun “tú” is rarely used; it’s reserved for intimate and romantic situations, which don’t apply to mafia culture.

Use of the pronoun “usted” is a little more complicated. Paisas reserve it for two extremes of the social spectrum: strangers or intimate friends/family members. For example:

- “Don Omar, soy yo, Manuel, el hijo de Irene, es que necesito hablar con usted una cosita”

Notice that in the example above there exists a large degree of unfamiliarity between the two characters. Manuel decides to implement the pronoun of “usted” to show respect to Don Omar, an older stranger.

- “¿Usted sabe cuanto debe valer esa chaqueta nueva?”

In this example, two close friends are holding a conversation. They decide to use the pronoun “usted” to show respect and intimacy.

Upon reading the two examples above, the audience understands that paisas value their relationships, and the address form used can set the tone for the entire interaction. These forms serve to indicate who is a “part of the group” and who is “outside of the group.”